In December 2010 – Gin & Dry a 15 minute short film was distributed across the UK to Picturehouse cinemas nationwide. The self distributed release by Capture, reached 10 cinemas and screened in front of multiple films such as The American, Gods & Men, Somewhere, and It’s a Wonderful Life in the lead up to Christmas – it was distributed entirely through the use of replicated DCP’s on low cost portable hard drives. It was one of the largest theatrical releases for a short film for many years.

This blog documents our experience so that those independent filmmakers who follow us are more informed as to how it all works. I wish I had had access to all the information contained here before we rolled out! In this blog I’ll relive our story and tackle these issues:

- What is a DCP?

- How do you create them?

- How we distributed Gin & Dry.

- What are the practicalities & benefits?

- Is Encryption/KDM worthwhile?

- What could (or should!) the future hold?

- + some useful links relating to the subject.

When we first came to distribute Gin & Dry we could not afford the substantial costs of a 35mm transfer, so when the opportunity to distribute to Picturehouse Cinemas nationwide came about we immediately turned to this new, exciting technology.

A BRIEF BIT OF BACKGROUND:

So firstly a little history and jargon busting. Around 1999-2000 the SMPTE (The Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) started a process of cross industry standardisation of Digital cinema – their aim essentially was to create an international standard as to what a DCP file is, presumably so that a filmmaker can make one DCP and then very easily replicate that across the world. In 2007 the UK Film Council spent £11.5million on installing 230 digital projectors in cinemas across the UK specifically intended to support independent non-mainstream films. The by-product seems to be that within the UK, that installation of new digital technology has made theatrical distribution more accessible to independent filmmakers and companies with smaller means.

The SMPTE then agreed standards in partnership with the ISO (International Standards Organisation) and this has only been in place from about 2009 onwards. “DCP” – stands for Digital Cinema Print and is a file based digital compressed copy (or ‘Print’) of a film taken from a digital master – The agreed standard is:

Jpeg2000 (Compression format) in XYZ Colourspace (XYZ essentially is a measurement gage that describe any colour in the spectrum)

4K – which is 4096 x 2160 or if its widescreen ‘Scope’ (2.39:1) 4096 x 1716 active image or Flat (1.85:1 – close to 16:9) – 3996 x 2048 …

…Or 2K res, which is 2048 x 1080 or if it’s widescreen ‘Scope’ (2.39:1) 2048 x 858 or Flat 1.85:1 – close to 16:9) 1998 x 1080.

24bit image sequence

48/96KHz audio (usually in wav. format)

.mxf file format with XML wrapper

CREATING THE GIN & DRY DCP:

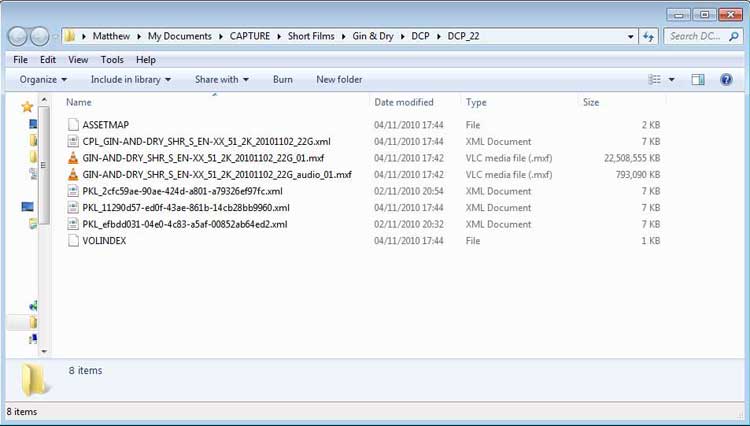

In the case of Gin & Dry we shot on a Arri D21 Digital Cinematography camera to a HDCam SR Clam shell recorder at HD 1920×1080 in S-Log. The Film was graded at Molinare in a baselight suite ingested & worked on as DPX-Log Files and then mastered to HDCam SR. HDCam SR can then be used to make all the necessary deliverables. To create the DCP we injested the HDCam SR tape, upresing the 1920×1080 original to 2k (2048×1556). The Hardware & Software to do this was a DVS Clipster – The transcoding time takes approximately 1/2 – 1/3 the length of the film – What we were left with looked like this:

8 files – essentially we have there – 2x mxf files in an XML wrapper (this is readable by the Cinema’s projector server which can understand its instructions)

The way it works is the Clipster converts your film to an image sequence of jpeg 2000 sequentially numbered image files ( file format .j2c) and then that image sequence is tied up in 1 image .mxf file which in turn speaks to an XML wrapper which explains to the Server/Computer on the projector how that image should be played. For Audio the Clipster ingests 6 different .wav files for a 5.1 surround sound movie and then holds all 6 wav files in 1 audio .mxf file, which also speaks to the XML wrapper. So the XML wrapper holds the instructions about how to combine the image file sequence with the audio file. The XML file also controls subtitling should the film require that.

ENCRYPTION OR NO ENCRYPTION?

When we supplied the DCPs to Picturehouse they asked us for a KDM, which means Key Delivery Message. This is a unique XML code which unlocks an encrypted DCP. The KDM also holds the time period/distribution window between which a film can be screened by the exhibitor. This is the part of DCP’s that can costs LOTS to make and then manage as the idea is that the KDM is never distributed with the DCP but is held by the distributor to allow the DCP to be played via remote servers and is the safeguard against DCP piracy.

We decided not to get a key (KDM) done at all. At the end of the day this is an independent movie, and as we don’t have the marketing budget of a studio distributed film we felt it was a silly step to encrypt our film as it would A: cost more, B: take up more of our time to distribute & replicate. We joked that probably one of the best things that could happen would be for Gin & Dry to be pirated as it would spread awareness of our little film! Does an independent film really have to worry about this? I think not.

Most Studios insist on encryption using either Clipster or QUBE due to concerns over security /piracy. They also have the budgets to spend on multiple KDM encryptions.

REPLICATION & DISTRIBUTION

So once we had our DCP we went down to the Ritzy Cinema in Brixton and tested it.

Initially we could not get the server at the cinema to recognise the DCP at all. After discussions with the projectionists Jackie & Sam we discovered that the reason for this was rather simple. The 8 Files had been placed in a folder entitled “Gin & Dry DCP” nothing wrong with that you would think, but it turns out that for DCPs to be recognised by the DoReMi Projector Servers then the files must be the ONLY items on the drive – no sub folders – just right there on the drive. Once we’d sorted that out the file ingested/transferred onto the projector fine. The interface looks like this by the way:

What was interesting was the way these servers are completely remote – a couple of times when trying to injest the DCP, the projectionist could ring up Arts Alliance Media to see if they could help, and from a computer miles away in central London they were able to open up new areas of the server and move the mouse around remotely on the screen in front of us. Amazing stuff.

We then checked the quality of the DCP on the Big screen, and it looked incredible. We had several “was that 35?” remarks from audiences – joe public cannot tell the difference. The only downside to digital I find is it either works or it doesn’t. There is no in-between, no random reel by reel issues. If the server recognises the film it plays in glorious quality that will never ever degrade no matter how many times it is played or moved between screens. If the server doesn’t recognise it, there is no film.

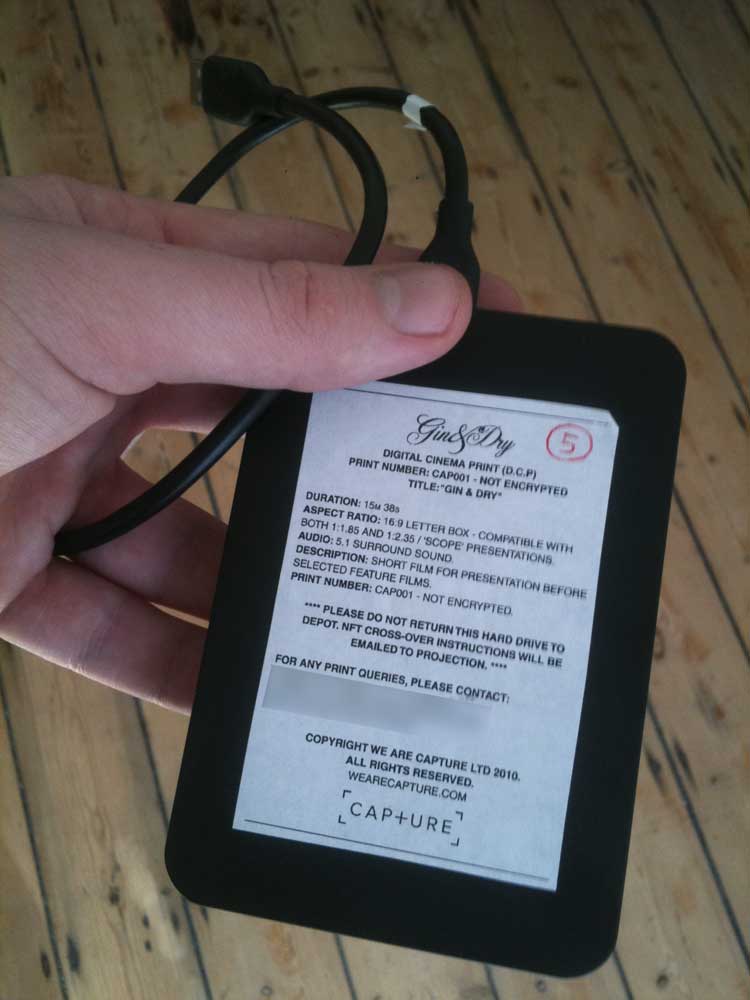

We simply copied and pasted the exact contents of the DCP master to 5x consumer small USB powered 320-500gb hard drives like this, labelled them up and then Picturehouse took control of those and distributed them physically across the country to sites in Brighton, Newcastle, Southampton, Henley and across London.

Even these hard drives felt too big to be honest. As Gin & Dry is a short film, the total combined file size of the DCP was 22gb for a 15 minute film. These days you can find tiny USB sticks with enough memory for that, which would save you a lot in terms of postal costs if you were self distributing nationwide or even globally on a big scale.

The great thing is that once a DCP has been ingested onto a server, no KDM means they can remain on that server in principle forever. Unlike a 35mm print, you don’t have to keep copies physically at the cinema as cinemas with multiple digital screens have the capacity to internally copy the film across from 1 screen to another, whilst the DCP is winging it’s way over to another cinema location for ingest. I worked out that you could easily take your film on the tube to every Picturehouse site in London and ingest the DCP into all their servers in less a day. Digital screens also have the capability to be wirelessly downloaded from a central server, removing any need to physically move hard drives around between sites. This costs more money as the bandwidth/server time is charged and can take many hours to download a film ready to play to a server. Our short took about 30 minutes to ingest at each cinema via USB 2.

RIGHT CLICK > CREATE DCP?

This is the future of theatrical distribution. I cannot see 35mm lasting much longer – it makes no sense at all to lug around massive 35mm reels when you can remotely drop a file onto a server. I can see in a few years time Final Cut Studio, Avid Media Composer, Premiere Cs etc allowing you to export a SMPTE/ISO standardised DCP direct from the grade. It has to happen. At the moment there are ‘home’ alternatives to systems like Clipster, such as EasyDCP which for an affordable price you can create them on desktop PCs.

I can see a future where the internet allows independent filmmakers to self distribute films to a theatrical level better than 35mm standard – direct to cinema owners, the only barrier will be convincing cinemas that your film is good enough and will bring an audience.

Big thanks to Soren Kloch – DCP specialist at Rack & Pinn for his guidance and help on the Gin & Dry release and on getting a grip on how DCP’s work.

Find out all about the film here

Matthew Jones

Producer | Capture

USEFUL LINKS:

The special edition poster with the cinema logos below: